A Doorway Opens

In genealogical research, as in many other fields of inquiry, a seemingly insignificant footnote can be a door into a fascinating episode of a subject’s life. When I revisited the facts of my 2x great uncle Francis Marion Moates’ life, my eye feel again on the back of the headstone application for U.S. Veterans. (See below.) On the front (recto) it listed his service in the Florida Infantry CSA. In verso it read “29 Nov 65 Corp. Co. E 3rd Reg US VOL INF,” that is, Honorably Discharged 29 Nov 1865 as a corporal in Company E 3rd Regiment of United States (i.e. Union) Volunteer Infantry.

Rock Island Barracks, Illinois: A Union Prison “hell-hole”

I had read in the records of the imprisonment of Pvt. F.M. Moates in Nov 1863 following his capture at Chattanooga during the Battle of Missionary Ridge, an event that transpired very near my daughter’s present home in East Ridge, Tennessee. He was transferred to the infamous federal prison at Rock Island Barracks, Illinois. During my review of my notes, I looked more closely at what life was like at Rock Island. In a (hyphenated) word it was a “hell-hole.” Historians identify it as one of the largest and most notorious Union prison camps during the Civil War. [https://www.mycivilwar.com/pow/il-rock-island.html] The prison opened in December of 1863, a few weeks after the Battle of Missionary Ridge, Tennessee where Private Moates was captured. During its operation a “total of 12,192 Confederate prisoners were held at the prison camp. . . . A total of 1,964 prisoners died.” This is a causality rate of 16%, a fraction comparable to the death rate during the battle in Chattanooga itself in which he was captured. (8,000/48,900 CSA). [https://home.army.mil/ria/about/history]. Thus, imprisonment did not spell safety; on the contrary, it threatened continuing peril and hardship.

Rock Island Barracks, Illinois

Pvt Moates Takes the “Oath”

After a year of incarceration, Francis Marion Moates, who had been named for the revolutionary war hero “the old swamp fox” of South Carolina, “took the oath.” This was a serious, treasonous act. We, naturally, are prompted to imagine his motivation for this grave decision. He would have been regarded by his confederates as a despicable traitor to “the cause,” forever branded as “a White-washed rebel or a Galvanized Yankee.” Perhaps he was motivated by the opportunity to escape the potentially lethal conditions in prison. Alternatively, he could have been enticed by the offer of the $100 bounty for enlistment that he could forward to his family languishing back home in Northwest Florida. Furthermore, he probably had heard of the Union raid on his hometown of Eucheeanna (23 Sep 1864) where his wife and two children and his recently widowed mother suffered without provision following the raid. Winter likely would mean famine and starvation back home. Clearly, he must have inferred their desperate plight and perhaps saw enlistment as an expedient solution.

After he enlisted in the union army, he was—very probably—moved to a separate section of the prison as was standard procedure. This practice was for the protection of the inmate recruits against reprisal by their former comrades. Whatever Francis’ motivation records confirm his decisive action. Below is a photograph of his actual signature on his enlistment paper.

He’s in the (Union) Army Now

By spring his newly mustered unit, Company E of the 3rd Regiment of the Unites States Volunteer Infantry (USVI), was transported to Ft Leavenworth, Kansas for training and marched by stages to Ft Riley and on to the Nebraska Territory. Dispatches report that the 3rd Regiment arrived on the frontier at Ft. Kearney, Nebraska on 9 April, 1864 after an arduous journey. (See annotated map.)

On the Frontier at Ft Rankin/Sedgwick

Subsequently, Company E established its headquarters at Ft. Rankin, also known as Camp Rankin and later as Ft. Sedgwick, a few miles west of the township of Julesburg, Colorado Territory on the North Platte. His unit arrived about five months after an embarrassing and painful defeat of the troops garrisoned there. In a retaliation for the horrific massacre of Cheyenne and Arapaho men, women, and children at Sand Creek, allied tribes of Cherokee, Arapaho, and Lakota attacked the fort. By a cruel coincidence, the massacre occurred on the very day that Francis Moates enlisted over 700 miles east in Illinois. (29 Nov 1863) By at first feigning retreat, the native warriors lured the detachment of about 80 soldiers and 20 civilians out of the fortifications, then surrounded them. All but about 18 “Indian fighters” made it back to the relative shelter of the sod walls of the fort. Those that remained on the field of battle were dispatched by the warriors. The survivors stayed safe behind the earth works of the fort while the raiding party sacked the nearby town of Julesburg, pillaging for three days before burning it to the ground.

Francis and his comrades arrived at the fort about five weeks after the indigenous warriors had departed the immediate neighborhood. The new troopers were assigned to help complete the construction of Ft. Sedgwick and to provide armed guard for the mail coaches passing along the Platte. The march from Ft. Kearney, Nebraska to Julesburg, Colorado was an ordeal in itself. One commentator who made the trip within a few weeks of Pvt. Moates described it in a dispatch east thus: “After leaving Fort Kearney, we had an opportunity to witness for hundreds of miles the dreary monotony of the valley of the Platte. The river is now high and looks as if it might be navigable for steamers; but it is one of the most deceptive and treacherous of streams . . .” [Chicago Tribune, June 10, 1865 p 2]

Out of the Frying Pan into the Fire

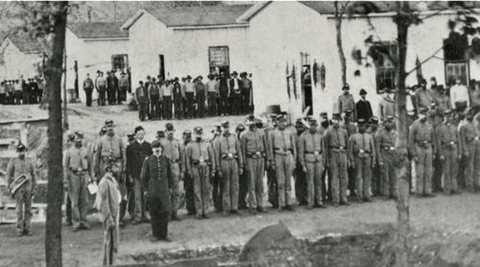

The ominous presence of deadly war parties surely weighed on everyone’s mind and prompted an exhausting state of hyper vigilance. Reports of raids, killings, and scalping were flying everywhere. And privation was the order of the day. If life at Rock Island Barracks was miserable, existence on the plains of northeast Colorado was even more dismal. Ft. Rankin (later Ft Sedgwick) bore the sobriquet “Ft. Hell.” The reader can judge for himself the accuracy of this characterization from an examination of a photograph of the post where Corporal Moates was billeted. Despite the privation (or perhaps because of it) Private Moates had been promoted from the ranks on 1 Aug 1865.

A sense of the awful condition is provided for all time by Brevet General James F. Rusling, who performed an inspection in September 1866 and reported to congress, “The general character of post buildings was found to be bad, and is believed to be a fruitful source of discontent, desertions. One post inspected had lost 25 men by desertion in one month, with their cavalry horses, accoutrements, Spencer carbines, complete, and many instances of this kind were reported to me. In fact, no humane farmer east would think of sheltering his horses or cattle in such uncomfortable and wretched structures, huts, willow-hurdles, adobe shanties, as compose many of our posts in the new States and Territories now…’ Rusling, James F. (30 June 1867). “Affairs in Utah and the Territories”. House of Representatives 40th Cong. 2nd Session. Mis Doc. No. 153:18–19.

One may recall that Ft Sedgwick was the inspiration for the derelict and deserted fictional post that Lieutenant Dunbar occupied in the movie Dances with Wolves. While many aspects of the movie fort are fictional, the producers got right the general state of dereliction of this desolate outpost where the 26 year-old Floridian found himself. (Check the links below for a deleted scene from the film that explains how the fictional fort became to be deserted.)

Mustering Out at Ft Leavenworth, Kansas

But Great Uncle Francis endured the hardship. Apparently, his unit was spared any major conflict during his time on the prairie. Only limited skirmishes are reported in his area during his presence in the region. He, nevertheless, faced crude accommodation, brutal weather, boredom, and strict military discipline ever under the threat of hostile attack. At last, on 29 November 1865, his year-long enlistment complete and the hostilities of the civil war winding down, he and the rest of his regiment mustered out at Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas.

Corp. Moates had drawn a pay $74.98 since his enlistment with a stoppage of $3.19 for damages to the property of Mr. John Mattis and others. There hangs a tale untold, we are sure. There are several individuals named John Mattis or Mattes who were immigrants from “Prussia,” that is, Germany, in Nebraska and environs that Francis may have interacted with. We can only speculate as to what were the events that left him responsible for property damage equivalent to three days wages or about $70 in present-day currency. Apparently, no dishonor accrued from the debt since Corporal Moates was mustered out with an honorable discharge.

Aftermath

The value of his and the service of his fellow “VOLS” is well summed up by Ronald Wirtz of the University of Nebraska.

“The 3rd U.S. Volunteer Infantry was only in service in Nebraska and points west less than nine months, and they left a frontier highway along the Platte that was still under serious and continuing threat from hostile Indians. Their contribution during that time on the frontier was not unimportant, however. They helped to stabilize a situation that could have become much more volatile by serving as a protective garrison force in strong points over a widely dispersed front. In company with a number of cavalry units, they built and maintained forts, posts, stage and telegraph stations, repaired telegraph lines, escorted emigrant trains, provided protection for private property, and helped to stock and manage warehouses and supply centers used by both civilians and the military. They were a stable and dependable force during a period characterized by unrest, insubordination, and even open mutiny among other military units in the region. It is fitting that they should be better remembered and honored for their service.” [“The 3rd U.S. Volunteer Infantry, Pt. 1: Galvanized Yankees Along the Platte,” Ronald Wirtz, University of Nebraska at Kearney https://openspaces.unk.edu/ctr-books/1/, accessed 28 Apr 2025]

Francis returned to his Eucheeanna home following his discharge, arriving by December, judging from the estimated date of conception of his third child, Emma. He came bearing his savings from his service that provided the resources he needed to pick up his life again. But he was a changed man, to be sure.

He appears in the 1867 voter registration list and the 1870 census for the county. We speculate that he resided in his boyhood home once more and began a steam saw mill and grist mill business in partnership with his brother James, who resided on the Dew property a mile down the road. But that is a story for another exploration in the full life of my great grandfather’s (James Marion Moates) uncle and name sake Francis Marion Moates. This story has enough drama and imaginative richness to evoke our sense of his character and experience.

He went to war a young man of barely 21 and returned five years later a much more mature veteran of two armies. He left a rebel and returned a Galvanized Yankee.

Links for future study:

Deleted scene of abandonment of Ft Sedgwick (fiction)

Ft Sedgwick (hitory)

Colorado War (Sand Creek Massacre etc.)