In this present age we are a rootless generation. On average, Americans change residence 11.7 times in their lives. [Source: https://www.steinwaymovers.com/industry-insights/ ] This statistic seems very plausible to me, since in my own childhood my parents relocated six times before I left home, and subsequently, I lived as a nomad myself—moving to sixteen “permanent” residences after founding my own nuclear family—a fact of which I have been reminded by my children, who themselves have itchy feet, as well. So it is not remarkable that I share with many of my contemporaries an inchoate longing for an old home place, a Heimat, lost. Recently, I came across a word for this emotion—hiraeth. This word is a unique gift of the Welsh culture, but is a universal experience, I believe. And having a word for a nebulous sensation somehow seems to give us a handle to grapple with it. I am persuaded that from time to time everybody experiences morriño (Galacian Spanish dialect for a longing for a homeland), or if we were Portuguese we might call it suadade, or even anemoia, the longing for an unknown home or that special homesickness for one’s ancestral home the Germans call Heimatweh.

Where to look for a home?

Whatever word we attach to this feeling, my genealogical research has raised the hope of uncovering my patrimonial estate or a homeplace (a Heimat?) that could be the nexus of my hiraeth. But along which branch of the family should I search? I was closest in distance and in affection to my maternal grandparents, Noah Theodore Webster Moates (1889-1972) and Katie Roberta “Bertie” Holland Moates (1888-1966). I learned in studying them that my grandfather was named for his great grandfather Noah Moates (1793-1864). My Pa died never knowing his grandmother’s father. Noah the Elder appears in the records of Montgomery County, Alabama in 1826 as a Justice of the Peace, barely six years after it became a state. His honor was enumerated in the 1830 Census for Montgomery County, Alabama, as well. In the next two decades his name resurfaces in the company of kinsmen who also emigrated from 96 District of South Carolina and were of French Huguenot stock. Noah (1793) as I often identify him, was the grandson of Jonathan Silas Motes, we believe. These family members of unestablished relation who also pioneered Alabama include Carey Motes or Moates, William (or William C) Motes, Elizabeth, Elihu, John, and John T. Motes, Moats, or Moates (a father-son pair we suspect.) Other relatives flooded into south central Alabama at about the same time, notably the brothers Morris and Dendy Motes. The name appears in various forms, as the orthography was unsettled in the 18th and 19th centuries. Historians suggest that the original form was Delamotte or a variant thereof. Nevertheless, in 1833 a clerk entered the purchase of a parcel of land that also appears in a Land Patent that is clearly Noah (1793). We can know precisely where the property was located because of the PLSS, the Public Land Survey System established in the US initially by the Land Ordinance of 1785. [Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Land_Ordinance_ooudaef_1785 ] The key features of this system are the descriptors township, range, and section. Each township is—usually—a square, six miles by six miles in extent with each square mile comprising a section of land. Thus the sections each consist of approximately 640 acres. The PLSS was the brainchild of Thomas Jefferson, who proposed the “Rectangular Land System” that was enacted into law as the Land Ordinance of 1785. [Source: https://mlrs.blm.gov/s/article/PLSS-Information ], barely eight years before Noah (1793) was born.

A Note on Locating Public Lands

In the PLSS, key baselines were defined at various latitudes. In south Alabama the principal baseline aligns with the border with Florida. Thus, the southern edge of township 13N lies 78 (13×6) miles north of the Florida-Alabama line. Likewise, meridians running north–south were also defined, such as the one passing through St. Stephens, Alabama from which ranges were numbered east and west in six mile increments. Thus, range 20E lies 120 miles east of the St. Stephens meridian. Below is a map (courtesy of Wikipedia) of the lands subject to the PLSS.

The public land was offered for sale by the Federal government (after having dispossessed the indigenous peoples who had collectively stewarded it for millennia). The 6×6 mile townships (containing 36 square miles) were subdivided into 36 sections of approximately 1 square mile (or 640 acres), each numbered in a consistent serpentine or boustrophedon (as the ox plows) pattern. Beginning in the northeast corner the sections are numbered consecutively first westward then eastward, alternating directions as shown in the illustration below. Section 6 is highlighted for special consideration.

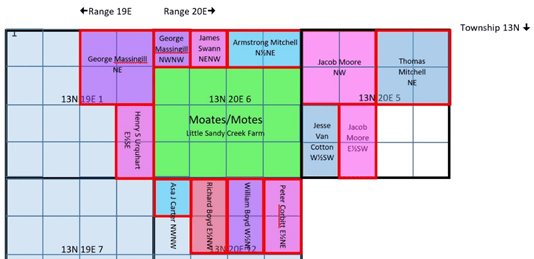

Such holdings were frequently too large an investment for the small farmer, so the sections were subsequently further subdivided into quarters, designated NE (northeast), NW (northwest), SE (southeast) and SW (southwest), each comprising 160 acres. Further subdivision was designed by halving (80 acres) or quartering (40 acres) the quarter section as E½ SW¼ (or ESW) as illustrated in the enlargement. Thus, ESW 13N 20E 6, means eastern half of section 6, township 13 north and range 20 east containing 80 acres. These PLSS designations can be correlated to modern property lines using various on-line resources.

Eighty Acres of “Virgin” Alabama Land

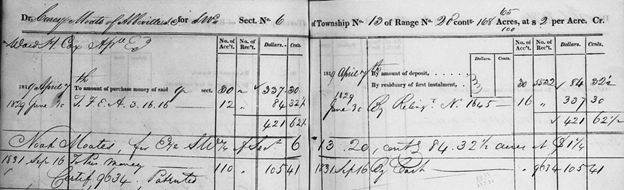

The choice of our example was not arbitrary. Indeed, in the land book from the 19th century we can see the land transactions that included Noah Moates. Notice the entry 3/4 down the page.

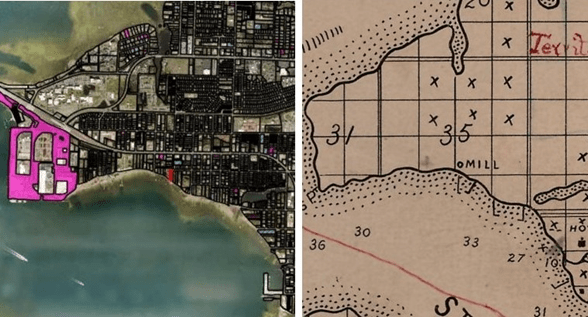

A close examination of the image reveals that in 1819, at the dawn of the statehood of Alabama one Carey Motes of Abbeville, South Carolina purchased the SW quarter of section 6 Township 13 [N] and Range 20 [E]. Subsequently, Noah Moates purchased the aliquot (a partial section) E½SW¼ of that quarter on 16 September 1831. The price was $1.25 per acre. Thus, he paid $105.40, a sizeable sum in 1831. The land was patented in 1838. A patent functioned as an official deed of ownership.

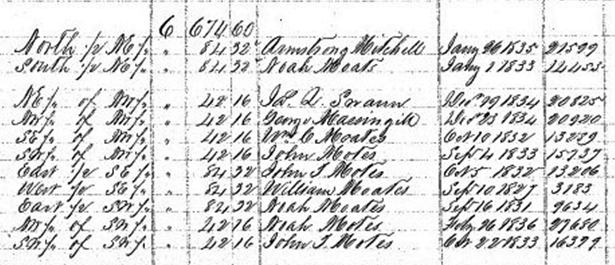

A later copy confirms that Noah not only purchased the land, but it also reveals his neighbors to the east were his kinsmen William Chesley and John T. Moates (aka Motes or Moats) with neighbors to the north and west to be Messrs. Armstrong Mitchell, Swann, and Massingill.

We believe that William C. Moates was Noah’s brother while John T. was his uncle, or cousin. Together the South Carolina immigrants formed an enclave, by the late 1830s, having bought up a patchwork of land parcels.

Below is a twentieth century topographic map of section 6, with the aliquots for Noah (1793) and his brother William Chesley Moates indicated.

Above is an overlay of the Noah Moates (1831) aliquot and the William C. Motes (1827) aliquot on a 1977 aerial photograph. We can discern houses (circled) and cabins that are made more visible in enlargement (below).

The Little Sandy Creek Farm (E ½ SW ¼ Section 6 Township 13 N Range 20 E)

Close examination places the GPS coordinates of the big house at 32.13193, -86.09279. There appears to be a well a few yards west of the Big House.

We can confirm that it is likely that Noah Moates (1793) resided on this land, dubbed the “Little Sandy Creek Farm,” before the census of 1830. He probably leased or rented the property from his relative Carey Motes in the 1820s. He was residing here in 1830 when the census was made. This we can infer by noting the order and subsequently location of the individuals in the census list. If we plot the location of all of the neighbors who appear in the census in order we see that the census taker meandered from farmhouse to farmhouse. Apparently, the enumerator missed the Noah Moates family on his first pass finding Chesley and John T at home but revisited the Little Sandy Creek Farm successfully a second time. Yellow designates the estimated trek before visiting the Noah Moates family (white circle) and the red arrows the path of the enumerator in successive visits to other farmsteads.

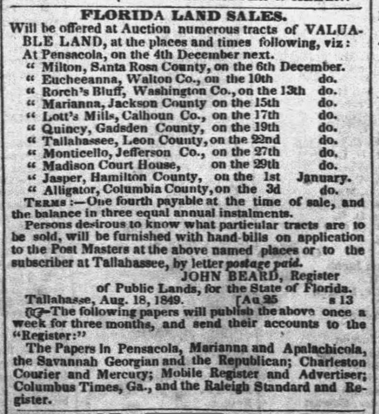

Noah Moates does not appear by name in any known census before 1830 and in 1840 appears in the census for Pike County while his son James W. Moates appears in Montgomery County, adjacent to his Uncle William C. Moates’ property. By 1850 Noah and family had moved to Eucheeanna, Florida, appearing in the census there. We can conclude that, most likely, Noah Moates owned and/or resided on the Little Sandy Creek farm from before 1823 when daughter Rachel was born in Alabama to about 1849 when they moved south. Thus, this is the first documented “homeplace” of the Noah Moates clan, although they occupied the site for only about 20 to 25 years before moving on. Therefore, is this not the “Ole Homeplace” of our family?

The Ole Homeplace Today

But what became of the Ole Homeplace and what remains of the place today? We can trace the history of the ownership of this tract of land down through the nearly two centuries by searching the property tax books and reading the newspapers for real estate sales. Sometime after 1850 the Little Sandy Creek (LSC) farm was sold to Mr. Martin Willis (1825-1866). We infer this fact from Elizabeth Moates’ (William’s wife’s) appearance as its manager in the 1850 agricultural census in a listing adjacent to William C. In 1866 Mr. Willis died. The property was inventoried in his probate records that also decree that, since the estate was insolvent, much of the real estate holdings were to be sold except for the tract reserved for his widow’s residence that corresponds exactly to the LSC farm. Sarah Ann Ingram Willis (1829-1895), widow and Martin’s heir held the property until her death in 1895. Her son Asa “Acie” James Willis (1860-1946) inherited the estate and sold it in 1899 to Thomas Jefferson Gray (1864-1937). T. J., farmed the property with his nephew William Chappell Gray (1901-1978) until Uncle Tom died. He bequeathed the farm to his nephew, since he had no surviving children. Chappell’s stepdaughter intimated in a private communication that T. J.’s siblings and other relations were upset by this bequest. Nevertheless, Chappell proved his mettle by his hard work for several years to pay off the outstanding debts on the property. Chappell Gray was a colorful character in his own right. He overcame a scandal from a scrape with the law as an alleged bootlegger to become a respected politician and prominent cotton farmer. At his death in 1978 title to the land passed to his second wife Frances Elizabeth Cason Bishop Gray (1912-1996), who subsequently sold the property in 1986 to Mr. H. R. (Robert) Dudley of Dudley Bros. Lumber, the entity that currently owns the acreage and manages it as timberland through a holding company.

I contacted a member of Mr. Dudley’s family who is a principal in the lumber company and obtained permission to “walk the property.” On Sunday 21 May 2023, my wife and I drove to the logging road entrance off Athey Road, Montgomery County, Alabama and I began my trek back into the past.

A Walk in the Woods

I had for weeks planned my excursion into the woods that surrounded the location of the Little Sandy Creek property. I had mapped our drive in our all-wheel drive Subaru along the logging road that peeked through the trees in the Google satellite views of the area. I carefully overlayed the 1971 aerial images with the corresponding Google images. My plan was to drive to the second clearing, where a white structure appeared to be, and then trek the 150 yards northward to the site of the antique buildings shown in the fifty-year-old aerials. Carolyn, my wife and partner would remain in the vehicle nearby.

We found the entrance to the property with only minor difficulty, but—how shall I put it?—nothing else went according to plan.

The first obstacle we faced was a locked gate.

If I had obtained access by borrowing a key, travel by automobile, even a four wheel drive like our Subaru Outback, would have been impossible. In at least three places, fallen timber blocked the track. Moreover, recent rains had filled the many unnamed tributaries of the Little Sandy Creek that traversed the road to produce potential impassable mud holes.

Along the way I started a doe. I realized one of the reasons for the locked gate. It was deterrence of unauthorized deer poaching. As further evidence, on the return trek I picked up a buck antler soughed off in a previous season.

So leaving my partner in the car at the locked gate your intrepid trekker (me) set off on foot to reach the site that his diligent study of the on-line maps indicated lay nearly a half mile into the woods. I had rehearsed the path in my imagination many times and felt initially confident that I could easily (and rapidly) navigate to the spot using my GPS-enabled Google Map. I did not count on the disorienting nature of the deep, unfamiliar woods or the change in the landscape since the last aerial photograph. Still I could draw on my dead-reckoning skills acquired as a youth traipsing barefoot about the swamps of my coastal Alabama childhood home. All began well as I followed the logging road, as I had envisioned from my armchair weeks earlier. I made it without incident to the first clearing, probably the site of the William Chesley Motes’ home two hundred years earlier. Nothing remained there except the grass-covered meadow. It was there that I took what turned out to be a wrong turn. I was led astray by an official-looking sign bearing a number 1 and an arrow. The sky was overcast so I could not readily discern the direction by shadows. The old bush wisdom of moss-on-tree-trunks-indicating-north was of no use since moss grew in abundance on all sides of the oak trees. Furthermore, my phone did not have a compass app installed.

I had promised Carolyn that I would check in frequently using our walkie-talkies that we had purchased for the occasion. It worked once when we tested it but I could not reach her subsequently, either because of technical difficulties or operator error. Minutes passed as I stumbled through the forest heading south (instead of west). At last, I reached what the number 1 alluded to: a plowed field. The field still appeared as a landmark on my satellite map. I realized that I had wandered farther afield in the wrong direction so I turned northward to hike and intercept the logging trail again. At that moment I recalled the sad stories my research had brought to light of the people who became victims of this very swamp. In September 1974 eighty-year-old Leatha Wilson was found dead not far from where I stood. Newspaper accounts of the event also alluded to the disappearance of five-year-old Willie Williams, who in 1969 ran into the swamp with his dog. His dog returned. He did not. He was never found. I suppressed the panic that began to arise that the victims must have felt. I focused on the map and the little blue dot that represented my position and verified that I was now moving toward my goal. I also heard the sound of traffic on the Troy Highway to my right. I also tried to keep an eye out for snakes and other dangers. But I overlooked, concealed in the under growth, a fallen log that caught my toe. I fell face first into the leaf litter. As I lay on the soft ground, just then my phone chimed a notification of an incoming text. Carolyn was worried. I replied with a cramped hand as I lay in the dirt, “Will tAlk soob” [sic]. Awkward is too kind of a description of my state.

Rising from my humbled position, I consulted the map. (See left below) It suggested that I return to the highway and drive to a different place and walk in again. I chose to bushwhack through the woods to the logging trail and thence on to my destination. I realized that the dark patches in the satellite were fens, natural swampy ponds that were persistent landmarks. Thus skirting the muck, I managed to return to the logging trail and ultimately to the second clearing that I had determined lay just south of the homeplace I had seen in the 1971 aerial photograph. When I arrived at the clearing, the little white building I was expecting was gone. Only four concrete footings remained of what I had surmised was a storage shed. I was filled with renewed hope, however at the “ground truth” that my goal was within reach. I identified the path I had seen on the satellite view and proceeded up the path about 300 feet counting out the paces, left-foot-right-foot, 5 feet, left-foot-right-foot, 10 feet. Then I turned right and trekked about 100 feet into the woods. Surveying the understory, I caught sight of debris. Twentieth-century trash lay scattered about. Derelict appliances were strewn among the oaks and pines: a top loading washing machine, a bronze-colored refrigerator, a toppled gas range. Surveying wider I encountered the remains of a well that survived the demolition of the houses. It was a large diameter concrete culvert set vertically in the ground. I glimpsed the surface of muddy water about three feet below the surrounding forest floor. The GPS coordinates corresponded to those that I had concluded were those locating the well, as shown in the aerial photograph. This was indeed the place I had identified.

I brought out my trusty metal detector in hope of finding buried evidence of antique nails, a way to date a structure. In a few seconds of sweeping the area it sounded an encouraging “beep, beep!” I dug eagerly with growing anticipation. What came to light a few inches beneath the surface is shown in the photo below (left). The object that I uncovered was a tricycle wheel with a rubber tire through which a large tree root had insinuated itself. The find discouraged further metal detecting. My calculation was that there would be too many “modern” objects that would mask any earlier objects. A thorough scan would consume all the time I had remaining in fruitless searching. Nevertheless, I wanted to document what I had found as best I could. I retrieved my soil corer and extracted a sample (right). It revealed a black topsoil layer of about 4 inches (10 cm) deep overlying an abrupt transition to sand. This finding suggested that since the homeplace was abandoned in the late twentieth century, the composted leaf litter has built up at about 5 mm per year or more. In 200 years any artifact might be buried as deep as a meter (40 inches). I was not prepared for an archeological dig. From the soil core I concluded that before the demolition of the house in the late twentieth century the soil was probably barren packed sand. Later, as I reflected, I realized that the find, a child’s toy, was evidence that the house that had stood on this spot had been home to a family, perhaps a tenant, in the era when the property was owned by Chappell Gray. Perhaps the child, who rode what is now a relic of at least a half century vintage, was known to Leatha Wilson and might have been a playmate of Willie Williams, as well.

A low mound caught my eye. I moved closer and observed that it was a pile of rubble. “The remains of the chimney,” I thought. Indeed, the pile was substantial: about three foot high and eight to ten foot in diameter. I extracted representative samples from the debris pile. I thought to myself, “These will be helpful in establishing when this house was built.”

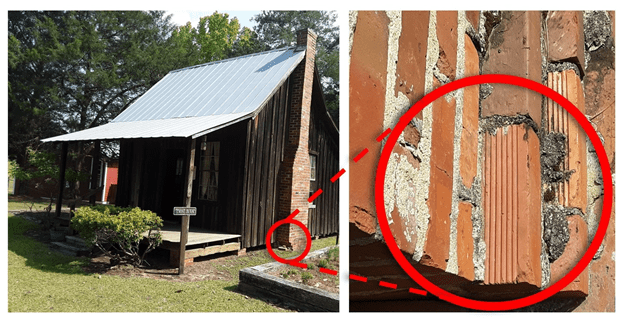

Later I documented the bricks with detailed photographs that I shared with various experts in the field of brick making and masonry. Below is a montage of a representative half brick. Close examination reveals ten V-grooves running the length of the brick as well as telltale longitudinal scratches, except at the ends where I noticed vertical striations that suggested the clay had been end cut.

The Tale of a Brick

Later that same day, when we visited the Pioneer Museum of Alabama in Troy, we observed similar bricks appearing in a reconstructed tenant house on the grounds of the museum. We ultimately ascertained that the original structure(s) stood on the Segars Plantation in Troy. Hugh Richmond Segars was granted a patent for the farm in 1851. Thus, we concluded that the bricks, if indeed they came from the Segars Place, must date from after the mid-1850s.

As I was composing this post, I had an illuminating discussion with Mr. Don Adkins of Old South Brick and Supply, Jackson, Mississippi, a vendor of vintage and antique brick. From the photographs and description that I had sent him he was able to determine that the bricks were fabricated by the stiff-mud-extrusion-end-cut process that was employed by Jenkins Brick Company of Wetumpka and later Montgomery, Alabama, beginning in the late 1890s. He opined that the bricks could not be any older than 1895 because the extrusion process was only patented in 1863 and took decades to gain currency. In 1899 the Jenkins Brick Company that used the method of brick making was incorporated in Wetumpka, Alabama, north of Montgomery. Bricks from earlier periods would have been hand molded and probably would not have survived the damp of the swamp, since they were low-temperature fired and lacked much vitrification. He further remarked that the age of the bricks did not negate the possibility that the house had been built earlier, since it was common practice to tear down failing chimneys and rebuild them with newer brick. Thus, all we can say is that very little remains of the original homeplace except for the land. The cleared space where the late 19th century structures stood is in the process of returning to its pre-habitation condition. Studying the photograph of the site below, we see smaller diameter hardwoods estimated to be less than 50 years in maturity. The 1820-vintage buildings of the Noah Moates family have vanished, victims of the ravages of Nature and of subsequent “improvements” by succeeding occupants of the land.

My children expressed their concern that I would be disappointed by what I found in my search to satisfy my hiraeth. I assured them that I did not know what to expect, so anything would be acceptable. What I found was a sense of the presence of my ancestors. The land originally was verdant and provided them with timber to build a log home, probably like examples of the two-room “Dog Trot” style common in central Alabama at the time. It was here that my great-great grandmother Rachel Moates, the mother of James Marion Moates (aka Miley), was born in 1823.

I concluded, also, that the land never really belongs to us. Not the earth, not the water, not the sky above. At best we borrow it from Nature. Indeed we belong to the land, the place of our nativity. It gets in at the root and works itself out in us and our children up the trunk of our family tree and out to the branches and needles or leaves as it does with the loblolly pine and water oaks.

Succeeding generations of men will—in the name of progress—obliterate every trace of our habitation. Likewise, Nature will reclaim her proprietorship if we do not continually maintain and restore the place. I am reminded of the dialog of the film Out of Africa in which Karen Blixen complains to Denys Hatton, her lover:

Karen: “Every time I turn my back it wants to go wild again.”

Denys: “It will go wild.”

In truth, the locale of my Alabama homeplace, my Heimat, has gone wild. All that remains is the earth upon which they walked. Thus, I can think of no more appropriate talisman of my family’s presence in this space than a souvenir sample of the soil they trod centuries before. With the help of my grandson Elijah Matteson, age six, 5x great grandson of Noah Moates, I prepared 2 dram (about 7 cc) labelled samples of soil that I had collected at the site, accompanied by a certificate of provenance and authenticity. Below is a photograph of one such sample with the certificate. They lie upon an antique depression-era table, factory built over a century ago, and refinished for my mother Audrey Moates Matteson (1926-1998) by my grandfather Noah Theodore Webster Moates (1889-1972) over a half a century ago during my memorable summer with my beloved grands. It is the people that make a place live in our memory. It is this longing for knowing them and touching them where our hiraeth becomes palpable. In knowing the place where our roots lie, we know ourselves a little better. Being there was worth the effort to get there.